Starlink V2 Gets Grant

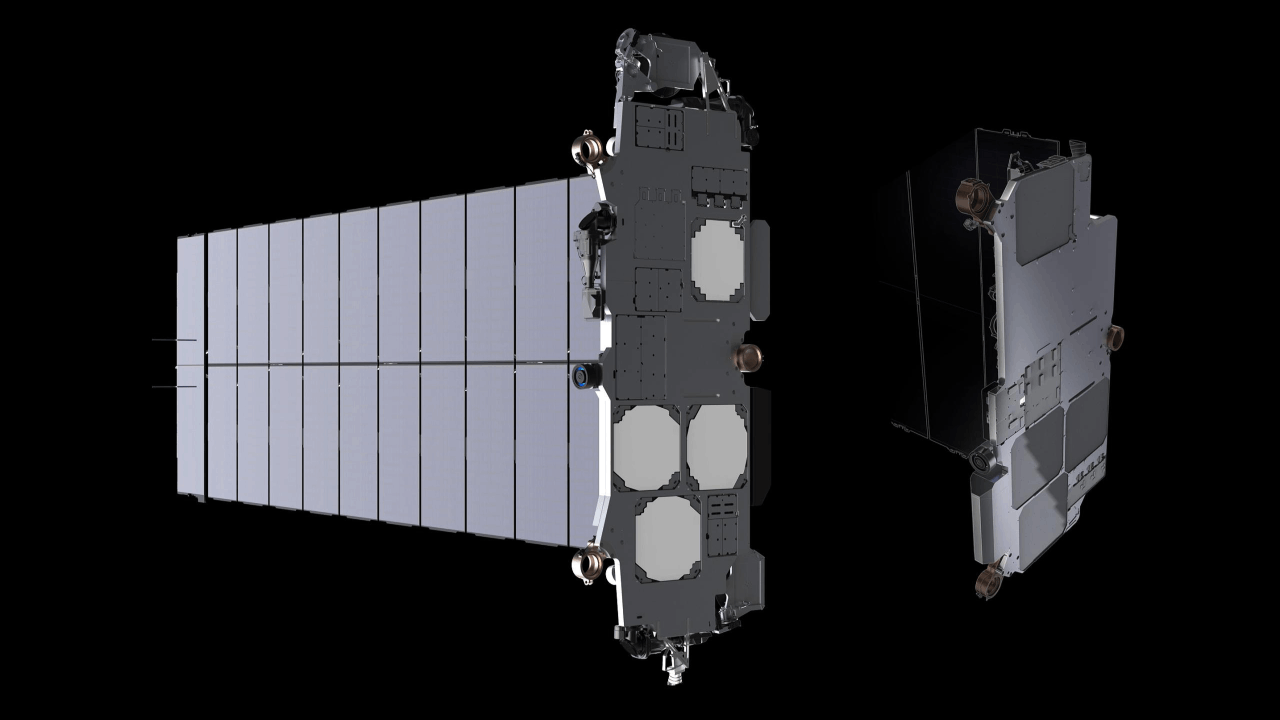

SpaceX has finally received a licence from the US Federal Communications Commission to launch and operate their new Starlink Version 2 satellites - but it’s not a cause for celebration.

The long-awaited FCC grant has been in the works since May of 2020, and while SpaceX applied for a licence to launch almost 30 thousand units, the FCC has only allowed for 7,500 - and will defer licensing the rest of the requested satellites until “further review and coordination with Federal users.”

That is a huge blow for SpaceX, who has been building their platform towards the goal of upgrading their Starlink constellation to the upgraded model - even outfitting their prototype Starships with dispenser-devices made specifically for the V2 satellite.

As usual, the FCC didn’t give much information as to how they arrived at this number of satellites, but their brief mentions several factors that went into the deliberations - some of which are very strange. However, the biggest recurring issue that the FCC seems worried about is reducing the number of satellites in orbit.

The issue of orbital clutter has gotten a lot of attention in the past year or so, spurred on by events like the November 2021 Russia anti-satellite test that destroyed one of their old orbital units - and causing months of near misses with the International Space Station.

Launch debris has also spurred calls for regulation - most of us probably remember China haphazardly deorbiting two of their Long March boosters over populated areas in 2021 and in November this year. But more and more countries and launch startups are putting vehicles into space - and adding to the amount of traffic and debris.

And the US government has been making an effort this year to study and curb the use of mega-constellations in an effort to ease this strain on our orbit. In September this year, the FCC itself pledged to modernise the rules on space junk in response to the Russian satellite incident - as well as complaints from astronomers who warned against increasingly large amounts of satellite constellations - as the objects interfered with observations and the search for potentially dangerous asteroids.

So the orbital clutter issue is the most likely reason for the additional time spent on licensing the Starlink V2 - as well as the very restrictive number of allowed units. It also handily explains why the FCC allowed for less V2 satellites than their 2018 authorization for 7,518 Starlink Gen 1.5 units.

In that instance, the FCC had taken only five months to process - but that was with a satellite that was already in regular use, and well before the extra scrutiny on orbital clutter.

But SpaceX has already gone to some effort to reduce concerns in these areas. Back in 2019, the company began testing to see if they could reduce the reflectivity of their Starlink satellites, and they began setting lower altitudes to help with the clutter issue.

The FCC has been curbing the use of constellations above 1000 km, because at that altitude, it could take satellites hundreds of years to de-orbit. Meanwhile, the majority of SpaceX’s requests for deployment zones has been around the 600-340 km mark - meaning any failed satellites would take under five years to de-orbit - which is what the FCC is targeting as of September this year.

And if the FCC was just being careful in how they apply their new protocols for constellations, that would be understandable. But there’s a bit in the FCC ruling that is… troubling.

When referencing the decision to cut the Starlink V2 numbers down to a fraction while they do more research, the FCC openly states that they made their decision based on a letter from Amazon’s Project Kuiper - the Amazon mega constellation project which is a direct competitor to SpaceX.

The 3-page letter expresses concern over not just the sheer number of satellites SpaceX wants to put up, but that it doesn’t allow for much room for other companies to put up their satellites in FCC compliant orbits. The letter goes on to suggest a number of options for solving this issue - including the reduction in satellites which the FCC went with.

And there are actually some good points here. If this letter had come from NASA or an independent source, it would be much less problematic. But it’s not a great sign that the FCC is taking recommendations from a competing company rather than an independent entity.

And the strangeness doesn’t stop there. Included in the partial grant is an arbitrary metric that could force SpaceX to “cease Satellite deployment” if the total deorbit time of any failed satellites in this proposed constellation reaches 100 years. Which means, if just 20 satellites fail at an average altitude of 500 km, SpaceX would be forced to stop deploying their constellation until the FCC has time to review the sources of failure.

This extremely draconian rule reportedly comes from a third-party company called LeoLabs - which is a radar-tracking service for low-earth orbit objects.

To be fair, getting metrics from a company like LeoLabs is less strange than going to a SpaceX competitor, but the current run of Starlink satellites have had about a 3% failure rate as satellites become unresponsive, and begin to de-orbit - which is relatively low for industry standards. But if that trend holds with this 7500 Starlink V2 batch, the attrition would be around 255 units - and SpaceX would have to halt before even finishing this batch.

It’s hard to say where the FCC and SpaceX will go from here. SpaceX is really relying on Starlink V2 to upgrade their coverage in the coming years, and it represents a huge investment. SpaceX isn’t a stranger to working with the FCC, so maybe they can get some wiggle room in the future.